The global technological rivalry between the United States and China may soon enter a far more disruptive phase. In a potential policy shift with sweeping global implications, the Biden administration is reportedly considering export restrictions on software built with American technology—a measure that would signal a profound broadening of the United States’ strategy to constrain China’s technological ascent.

While previous efforts focused on halting China’s access to advanced semiconductors and chip-making machinery, the new proposal targets the intangible yet omnipresent layer of the modern digital economy: software. From embedded AI algorithms to software used in designing and operating complex hardware, the scope of affected technologies could be vast.

From Chips to Code: A New Front in the U.S.-China Tech War

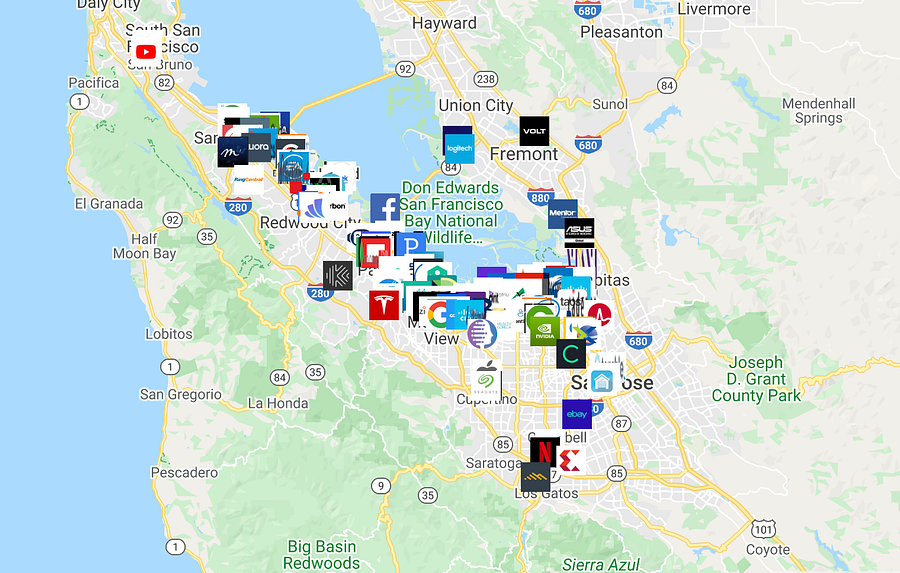

The move under consideration would restrict exports to China of goods, platforms, and digital services built using American-made software or development tools. That includes not just the software itself but any end-products developed using U.S. programming frameworks, simulation tools, AI modeling software, and automation suites—many of which are global industry standards.

This would represent a significant expansion of U.S. export controls, similar in logic to the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR), which has been used to restrict Huawei’s access to chips designed or manufactured with U.S. technology. The new policy would essentially extend those restrictions to any software-enabled technologies.

According to insiders familiar with the matter, the Biden administration is still weighing the exact contours of the restrictions. However, the direction is clear: a shift away from hardware-only policies towards a comprehensive software-based containment strategy aimed at undermining China’s ability to build, deploy, or export advanced technologies.

Strategic Intent: Curbing China’s Digital Momentum

At the heart of this proposed escalation is a growing concern within U.S. strategic circles about China’s rapid progress in AI, quantum computing, and autonomous systems—much of which is powered by software ecosystems that rely heavily on American intellectual property. Chinese firms, although cut off from leading-edge chips like those from NVIDIA, are increasingly turning to domestic alternatives and innovative workarounds. However, many of these efforts still rely—directly or indirectly—on software frameworks, libraries, and design suites originating in the U.S.

By controlling software, the U.S. could strike at the enabling infrastructure of Chinese tech innovation. This includes AI training models, CAD software for chip design, simulation tools used in military and aerospace applications, and code libraries essential for developing secure operating systems.

A senior U.S. official, quoted in recent reporting, stressed that “everything is on the table,” emphasizing the seriousness with which Washington views this strategic pivot.

Retaliation for Rare-Earth Pressure?

The timing of this policy consideration may not be coincidental. China recently imposed export controls on rare-earth metals critical to defense and semiconductor industries—a move widely seen as a geopolitical lever in the ongoing tech standoff. In response, the United States appears ready to retaliate by targeting China’s software dependency, a far less visible but equally critical component of technological sovereignty.

Rare-earths are essential for manufacturing high-performance magnets used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and missile guidance systems. The Chinese restrictions sent alarm bells ringing in Washington, prompting officials to explore asymmetric countermeasures—where the U.S. holds undisputed leverage, particularly in software IP and cloud-based tools.

Potential Scope: Everything Runs on Software

The possible scope of these restrictions is staggering. Consider the following examples of technologies that could fall under the new rules if implemented broadly:

- Industrial automation systems used in Chinese manufacturing, powered by U.S.-built PLC software.

- AI development platforms leveraging TensorFlow, PyTorch, or other U.S.-origin frameworks.

- Chip design software (EDA tools) used to create Chinese semiconductors, many of which still rely on platforms from U.S. companies like Synopsys and Cadence.

- Aviation control systems, energy grids, and satellite software—all potentially developed with U.S. code or running on U.S.-derived architectures.

Even smartphones, medical devices, and network equipment could be affected if they include firmware or systems built with U.S.-origin code.

The risk is that such sweeping controls could impact not only Chinese firms but also multinational corporations that build or assemble products in China, threatening global supply chains and potentially causing significant collateral damage.

Enforcement Headaches and Unintended Consequences

Despite its strategic appeal, implementing and enforcing such a policy would be extremely complex. Unlike physical goods, software is not always traceable, and its use is often deeply embedded in multiple layers of a product’s development and deployment cycle.

How does one determine whether a Chinese-made drone or smart home device includes American software IP? Even defining what qualifies as “U.S.-origin” software could prove legally and technically challenging.

Moreover, enforcing such restrictions could drive software development underground or toward alternative, open-source ecosystems. Chinese companies may accelerate efforts to build homegrown equivalents or shift toward European, Russian, or Indian software ecosystems, potentially splintering the global tech environment into rival digital blocs.

Risks for American Firms

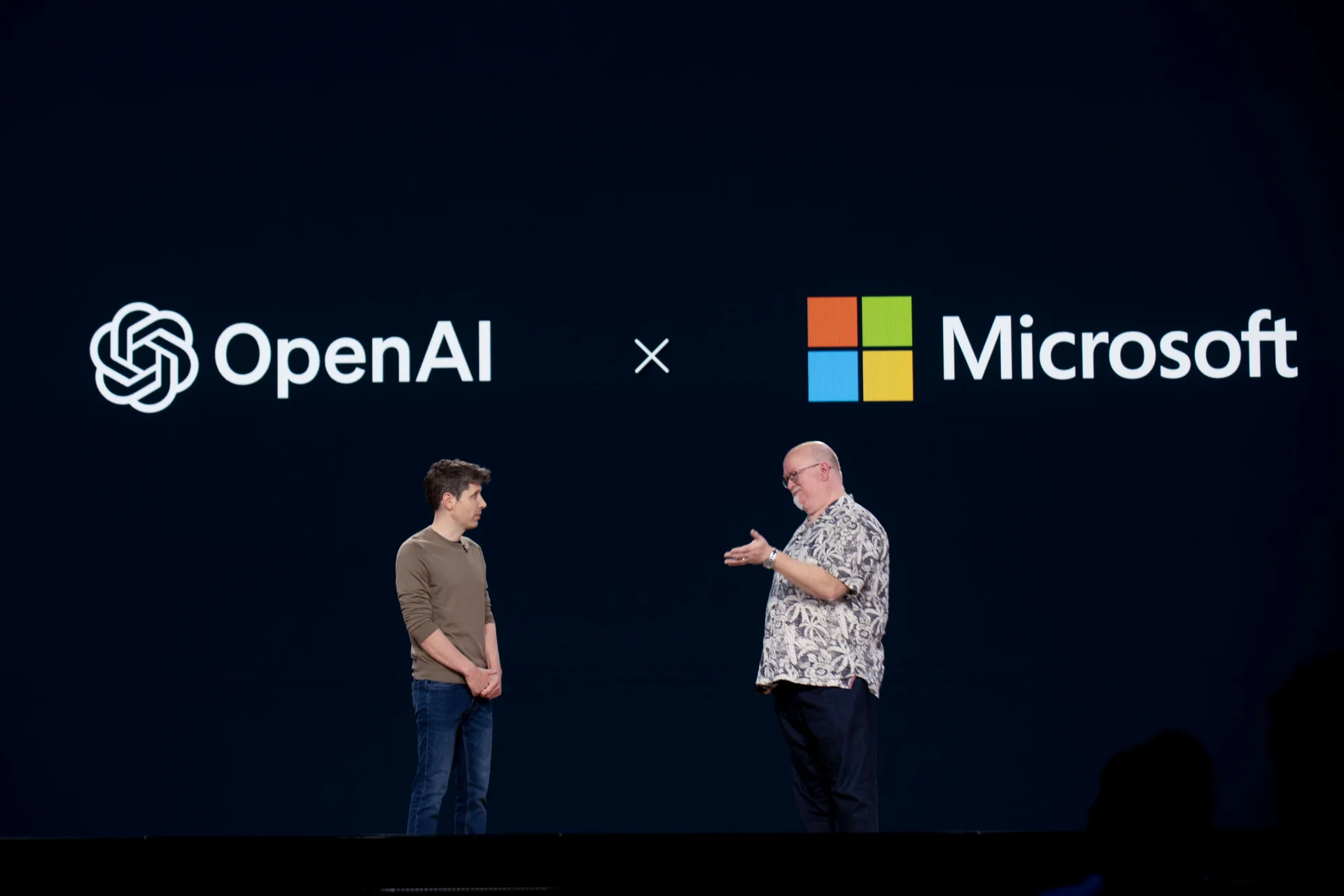

U.S. companies may also pay a price. Export restrictions would limit their access to the world’s second-largest economy, and the compliance burden could deter global partnerships. Firms like Microsoft, Adobe, Autodesk, and others that license software globally may face regulatory uncertainty, lost revenue, and operational headaches.

Past sanctions have shown that U.S. tech dominance can be a double-edged sword: when access is weaponized, competitors look elsewhere. Over time, the policy could encourage de-Americanization of the global software stack, undermining long-term U.S. influence.

The AI Arms Race: Software as the New Battlefield

This development is the clearest signal yet that the AI arms race is no longer about who controls the chips—it’s about who controls the code. As AI models become more complex and increasingly integrated across sectors—from surveillance to military command systems to autonomous infrastructure—controlling the software layer becomes a strategic imperative.

The decision, if implemented, would redefine the concept of digital sovereignty and elevate software IP to the level of national security infrastructure.

What Happens Next?

- Regulatory Framework: The Commerce Department and Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) would likely craft new rules. If modeled after FDPR, they could apply extraterritorially to any product made with U.S. software.

- Industry Lobbying: Tech giants and industry groups may push back, warning of economic fallout or unintended consequences.

- Global Coordination: Allies may be consulted, particularly those hosting U.S. firms or relying on similar export control regimes.

- Chinese Response: China is expected to retaliate—possibly with countersanctions, technology substitution policies, or even stricter data localization and cybersecurity rules targeting U.S. firms operating in China.

Conclusion

This potential U.S. crackdown on software exports marks a fundamental escalation in the technology conflict between Washington and Beijing. It is a bold attempt to assert digital control through intellectual property, particularly in areas where the U.S. still maintains supremacy. However, its long-term effectiveness and consequences remain highly uncertain.

Whether this becomes a turning point in the AI arms race or a cautionary tale of overreach depends on how the policy is structured—and how the global tech ecosystem responds.